Wednesday, 26 December 2007

The Diary

In September I finished the transcription of the official war diary of the Matron-in-Chief, France and Flanders, the original document being held at The National Archives in class WO95. Many unit war diaries run to a couple of hundred pages at the most, but this is a truly massive document, with more than 3,600 pages and over a million words; perhaps it can be more easily understood as the length of about 13 average length novels joined back to back. There are not many official documents which outline the day-to-day life of nurses in France during the Great War, and this certainly seemed a great opportunity to make available information about the workings of the nursing services during the period. Publication in book form rapidly became a non-option; unless it was stripped and edited within an inch of its life, it would remain an unwieldy beast, and such an editing process would veer completely away from my original intention of making even the 'boring bits' available to all, leaving just its skeleton behind.

So I decided to put it online on my Scarletfinders website (link on the right-hand menu) and began the process of turning my Word document into web pages. Unfortunately this isn't a simple job of cutting and pasting from one into the other, but I've managed to work at a steady rate and am currently working on June 1917, so nearly three years down and a couple more to go. From the beginning of 1917 the content of the diary expands massively, so three years of the diary isn't even half the work, and it means a great deal more to come, but on the whole I'm happy with the way it's going. I've already received quite a few emails from people who are finding it interesting/helpful, and I hope it will become a useful resource for all sorts of different reasons. But if I am a bit quiet here, it's just a sign that I'm usefully occupied elsewhere!

Thursday, 27 September 2007

Etaples and Camiers

Here are three photos from the aforementioned trip - I did warn that they are not the most exciting ever taken! The top one is taken looking straight across the site of 24 General Hospital, Etaples from Avenue du Blanc Pavé - this was where Vera Brittain worked as a VAD during her time in France.

The middle one is 20 General Hospital, Camiers, now a piece of waste land, but the scene of a lot of hard work and suffering 90 years ago.

The bottom photo is taken from the footbridge over Dannes Camiers Station, showing the old sidings running alongside the road which bordered 8 Canadian Stationary Hospital, and Nos.4 and 20 General Hospitals.

Wednesday, 26 September 2007

Etaples - the hospitals today

Many of the sites are now covered with modern housing, and the rest either forested, scrubland, or building plots, but the layout of the roads is almost identical, so it's at least possible to say 'No.46 Stationary Hospital was here', or 'No.51 Officers' Hospital was there...'

Camiers, three or four miles north of Etaples is rather different, as it has not been subject to the same amount of building, and the old sidings running in at the side of the station, parallel to the site of the hospitals, are still there, and standing on the station bridge it's possible to let your imagination flow backwards to a time when it was filled with ambulance trains, stretchers and casualties. It was certainly an unusual few days which produced an odd assortment of photos - suburban roads, houses, dense forest and piles of builder's spoil, but well worth it for someone who wears two anoraks at a time.

One warning though - if you intend to visit Etaples, please make sure you enjoy fish. The restaurants are good - some are very good - and they are very proud of their fishing history, and their fish, and their fish market, and their fish restaurants, and the fish starters, and the fish main courses...

Friday, 7 September 2007

Up and Running

To see the new content, go to the Scarletfinders site, and follow the links for 'Great War Accounts'.

Scarletfinders

Thursday, 16 August 2007

On the Horizon

So I've recently taken the decision to publish many of these documents, including the diary, on the web, and am just in the process of trying to work out what form they will take, and how to get them into readable shape. Because they are Crown Copyright documents, I'm free to do with them what I wish [more or less], as long as I don't use any actual images of them, and I acknowledge their source in full. Besides the diary, there are many accounts of the various nursing services during the Great War, including all the overseas nursing services who worked alongside the British. In addition, I've recently acquired copies of many WW2 personal accounts, written by members of QAIMNS and the Territorial Army Nursing Service, and one document giving the locations of all British General Hospitals at home and abroad between 1939-46. I'm not sure how long it will be before the first bit appears online, but hopefully not too long - in view of both the length and depth of the work, it will be a long, ongoing process, but I feel very excited at the thought that the documents will be available for all to read, learn from, and enjoy.

Sunday, 12 August 2007

A 'V.A.D.' at the Base (Part Two)

A 'V.A.D.' at the Base

by K. M. Barrow

On the other hand, in spite of all the pain and heartbreaking tragedy, the humorous side of life is never far away in hospital. One recalls the dummy – carefully charted and hideously masked – which was tucked into bed for the benefit of the V.A.D. and orderly when they came on night duty, and the stifled laughter under the bedclothes in adjoining beds. One recalls, too, the great occasions when some Royal or notable person came to visit the wards. Then we spent ourselves in table decorations, emptied the market of flowers, or ransacked the woods and meadows for willow or catkins, ox-eyed daisies or giant kingcups. Incidentally, we made the boys’ lives a burden to them by our meticulous care in smoothing out sheets, tucking in corners, and repairing the slightest disorder occasioned by every movement on their part, till the occasion was over. Sometimes the expected visitor did not turn up, and when another rumour of a projected visit was brought into the ward by a V.A.D., she was hardly surprised to find that her announcement was greeted on all sides by the somewhat blasphemous chorus of “Tell me the old, old story.” It was a curious coincidence, too, that on one occasion when the Queen was going the round of one of the wards in France – which was crowded with men fresh from the trenches – Her Majesty should have happened upon a patient standing stiffly to attention, and when sympathetically inquiring how he received his wound, was doubtless slightly surprised at the brisk reply, “Kicked by an ‘orse, mum.” On another occasion, when a visit from Sir Douglas Haig was momentarily expected, an intrepid Australian, concluding that there was time to spare, and greatly pleased to find that there was no competition, had placed a tin plate containing an egg to fry on the newly polished stove, which shone with inky radiance – the combined effort of orderly and patients. The decoration caught the eagle eye of sister, who demanded its instant removal, and while the discomfited cook seized his plate, the announcement, “Duggie’s here” was whispered; in his agitation the Australian turned the contents on to the polished surface. As the gallant Commander-in-Chief entered the ward he was confronted with a strong smell of cooking “gang agley,” and a stifling thick blue smoke rising like incense from the top of the stove. These Royal visits were much enjoyed by the men, and in the case of an Irish lad were the cause of much boastful comment as to the ease of manner with which he intended to greet the Royal visitor. These usually began with, “Sister, I shall just say to her” – and so on; but when the gracious and kindly lady did in fact stop to greet the boy, he was frozen stiff with shyness and terror; the flow of conversation with which he had intended to greet Her Majesty was conspicuous by its absence.

One of the things which struck one most was the eager championship of Tommy towards any patient of different nationality to himself. The black man was an especial pet and was treated by the boys as something between a spoilt baby and a pet dog. Sweets and cakes were showered upon him, and his simplest remarks were greeted with appreciative and indulgent laughter. Though “Darkie” was occasionally asked whether he had “been robbing the hen-roost lately,” or mildly ragged, he knew perfectly well that, had he got into trouble, the ward would have been solid in his defence. I have seen the men rush to get bread and jam for an immense, and I must own unattractive coloured man who would shout lustily for the latter, and would clear out a tin of “plum and apple” at a sitting – if he could get it. On one occasion, in Malta, when a valuable watch was lost, there was a regular chorus in defence of “Jose,” the little Maltese who scrubbed the verandah.

"It wouldn't be our old Jose, sister," they declared with conviction; although later this particular Jose proved, alas, far from being above suspicion. Even the foe came in for this kindly feeling in hospital when he was down and sick. I have heard a V.A.D. tell how she found a little group laying an unfamiliar game of cards with the quondam enemy.

"You see, sister," they explained, "we're playing it the German way, because of Fritz. Poor old Fritz".

Christmas is a delightful time in hospital, and though it was always specially gay in France for nurses, V.A.D.’s and patients alike, it was perhaps eastward on the other side of the Mediterranean, where gifts were not so numerous, and where Blighty was so far away, that the men looked forward to it most. It would be hard to forget the sound of the Christmas carols in the crystal beauty of the winter night in Malta, as a party of amateur performers, with swinging lanterns, went round from block to block of the great hospital buildings, while the patients hung over the verandahs or lay still and quiet listening in their beds. It would besides be difficult to forget how, as sisters and nurses went as quietly as possible from bed to bed during the night hanging the Christmas stockings over each, one head after another popped up like children, when they fancied no one was looking, to examine their little dole of presents – men who would, perhaps, never see another Christmas, and who had just been through the most awful experiences that man ever suffered.

It is, perhaps, the very simplicity and childishness of the British Tommy when he is sick and helpless, that has held so many V.A.D.’s to their posts in days gone by. Everyone who has been in hospital has noticed how even the middle-aged man seems to return to first principles in his last hours, and how the mother’s name was on his lips far more often than was either the wife or children’s name.

“Married, nurse?” said an Irishman, “Faith, and I’ve never met a woman yet who could be as much to me as my old mother!” And he was only one of countless others to whom “my old mother” represented Blighty, hope, and happiness all rolled into one. One saw this on night duty more especially, and it is of night duty in France, more than of any other time, that one thinks when one recalls old memories. Outside it was black as pitch, and the wind howled in the telegraph wires like the witches on Walpurgis Night, with perhaps the added sound of a bomb or the fall of shrapnel on the roof. Suddenly, through the war of sea and tempest, one caught the sharp piercing sound of a whistle, and after that the tramp of feet and the first soft thud of a stretcher being lowered to the ground gently for a moment. It was then that sisters, nurses and patients came into closer relation; it was then that the V.A.D. had wider scope in her work, and greater opportunities for learning and acting. Those on night duty were practically isolated from their fellows and thrown entirely on each other for companionship; and very pleasant was the morning walk and the morning bathe in summer, before bed claimed its sometimes unwilling victim, and the bright day was shut out and turned into night.

What we, perhaps, treasure most of all, now those times are over, are the autograph books which contain the signatures, artistic efforts, original or copied verses, which the patients supplied as souvenirs. These were more popular in the East than in France, and in one of the wards in Malta, an old volume of the Girl’s Own Paper, dating back to the “eighties,” provided the inspiration for many efforts. The picture of big men with a world of experience behind them, artlessly and laboriously copying pictures of apple-blossom and sparrows, or of an unattractive child with the legend, “Daddy’s blue-eyed boy” inscribed below it, represented a study in contrasts which was frankly touching. These were, however, real artists, and real poets who blossomed into eulogies of hospital and staff, or straightforward comments on their own experiences. Here is a sample which, as far as I know, is original:-

"There's a little place out East called Salonique,

Where they're sending British Tommies every week,

When you view it from the sea

It's a fine sight, all agree,

And you think you'll have a spree,

At Salonique!"

"When you're dumped upon the quay at Salonique,

And the smell that meets you there seems to speak,

You begin to feel quite glum,

And to wish you hadn't come,

For there's every kind of hum

At Salonique."

Another effor, which every V.A.D. will appreciate, began:

"The Red Cross Sister so demure,

On any chaps would work a cure,"

and ended up wittily and eminently satisfactorily from our point of view:

"To part from you will be a loss,

For you were never Red or Cross."

Sunday, 8 July 2007

A 'V.A.D.' at the Base

A "V.A.D." AT THE BASE

K. M. Barrow

“Keep the large things large and the small things small,” is a fine American motto which the V.A.D. abroad might well have adopted as her own. No matter what type of home she had left behind, every girl in the great military hospitals or elsewhere was living under strange, and at first, bewildering conditions. She was up against new problems and experiencing new sensations; she was confronted with new barriers and restrictions; but she was enlarging her horizon and expanding her outlook. Like Alice, it was as though she had stepped through the looking-glass into a new world. In spite of the pictures which it breaks the heart to remember; in spite of the little jars and frets and anxieties which seemed Gargantuan at the time; every V.A.D. all the world over could honestly write against the record of those days the words “very happy." Life in a military hospital is a school within a school. Inside the big school of experience there is a type of school life which is not unlike that life which we lived in our “teens” with its friendships, its “shop,” its frenzied activities, and its recreations.

Sunday was marked by two domestic features, namely, boiled eggs for breakfast, and afternoon tea in the sitting-room when we all ate French patisserie and home-made cakes like hungry school boys; and when even those on night duty sometimes made a belated appearance. It was by no means an infrequent occurrence up on the cliff, when a mess tent was used in place of a hut, for the whole to collapse when the wind blew “unco’rudely,” and to be found in the morning in a crumpled ruin like a collapsed pack of cards. On summer “half-days” we scoured the countryside for flowers for the wards, drank coffee and ate omelets in the old farm houses, or enjoyed tea and ices at the Club or in the cheerful French shops with their tempting confectionery, unless food restrictions happened to be acute at the time. Thousands of tired or convalescent V.A.D.’s will think more than gratefully of peaceful days in the lovely woods at Hardelot or in the Villa at Cannes; when expeditions were planned and everything that was possible done to give mind and body a real rest and a chance of recuperation.

Of the patients’ kindness and keen sense of gratitude, of their readiness to help in the wards, their goodness and unselfishness to each other, of their pluck and grit, and their cheerful assurance that they were “in the pink,” “not too bad,” or “fine,” even when the Angel of Death was standing close at hand, one need not speak. Had one had time to think, or the right to indulge one’s own feelings, the pathos of some of those scenes might have been unbearable. Pictures of a pale lad, singing “Annie Laurie” right through in a quavering voice, in his efforts to distract his mind from his sufferings during an agonizing dressing; of a “jaw-case” on the D.I. list with his poor mouth smeared with the crumbs of a home-made plum cake sent by his wife, which he had tried unavailingly or surreptitiously to eat; of a dying gardener with his face irradiated with joy when Sister handed him a flower, pass before one to be succeeded by another and again another, each unforgettable in its turn.

Thursday, 31 May 2007

Canaries

Wednesday, 30 May 2007

Life on an Ambulance Train 1917-18

WORK ON AN AMBULANCE TRAIN IN FRANCE, 1917-1918

by J. Orchardson

I joined an Ambulance train at Rouen in December, 1917, proceeding up the line to the Somme Valley. My first impressions were the extreme cleanliness, order, and brightness of everything on the train. The sisters’ mess, planned out of an ordinary railway carriage, was cosy and pretty, and our bedrooms most comfortable. Each train carried three sisters, usually a happy and contented trio. Our life was never dull, for those railways were the highroads of the war. Wherever we went there were troop trains, ammunition trains, food supplies, guns, tank stores; the never-ending accompaniments of a great campaign. Seldom were two days alike, no one knew where we might be sent next, or what adventure awaited us on the road. Our train might be in garage somewhere up the line, awaiting orders. All day nothing would happen and we would retire to bed at the usual hour. Suddenly there would be a bump, the signal that our engine had come on, and away we would go into the night wondering as to our destination. Wonder, however, soon gave place to sleep and we were content to leave place of call for the morning to disclose.

On loading at a Casualty Clearing Station, I was always struck by the rapidity and ease with which the patients were taken on and put to bed. I marvelled at their unfailing good humour, even when seriously wounded. They seemed to be so delighted to be on their way to the base, or perhaps to England, that they never failed to don a brave disguise. Somehow, I always felt more sorry for the walking wounded – that slow procession of pain with their white tired faces – but never a grumble or complaint. When loading was finished, our immediate duties were to inspect all the medical cards, diet the patients, and take a not of all treatments to be given during the journey; after this had been carried out, cigarettes, sweets, and books were handed round, and the sisters usually had time for a chat with the patients.

Our train was in the Somme Retreat of 1918, when the roads were crowded with retreating French civilians, leading their horses and cattle, and taking away what household goods they could carry. Old men and women, young women and children made a pathetic spectacle in that picture of retreat. The retreat began on March 23rd, 1918, and on the 25th the train was sent to Edgehill – a few miles from Albert – to load. We took the last patients from the Casualty Clearing Station at Edgehill and many straight from the field. The train was loaded to its full capacity; stretchers were put on the floors, in the corridors, in the two kitchens, and in the medical officers’ and orderlies’ beds. The train was held up for thirty-six hours but eventually reached Rouen. In April, the train was up north when the German offensive began and on several occasions took down a number of French civilians. ON incident was most pathetic. When the enemy broke through at Merville there was the usual retreat of French people. The train was stopped by some soldiers who asked us to take an old French woman whom they had found lying on the roadside. She must have walked many miles and was in a pitiful state. She said she was eighty-two years of age, and we recalled the old Hebrew’s saying about the years that only bring labour and sorrow.

Tuesday, 22 May 2007

Life on an Ambulance Train in 1914

LIFE ON AN AMBULANCE TRAIN IN 1914 by

The ambulance trains in 1914 were not the trains of joy and beauty which they developed into later in the war, anything that ran on wheels and could be attached to an engine was utilized in the early days of 1914. They were chiefly trains composed of wagons bearing the legend “Hommes 40, Chevaux (en long) 8,” so that the staff of No.7 Ambulance train thought itself lucky.

All the coaches on the train were entirely unconnected, and those nurses who have only carried out nursing duties on trains whose entire length it was possible to walk without once going outside, can hardly realize the inconvenience, sometimes amusing but at most times vexatious, to which one was put in 1914. Quite a number of teapots and cups and saucers came to an untimely end from the habit which the batman had of placing those articles on the footboard of the train when bringing the early morning tea; then, leaving them while he went back for something which he had forgotten – the train would start with a jerk – and “goodbye-ee” to tea for that morning. The greatest inconvenience of all was the difficulty of attending to the patients, and the vexation of spirit occasioned when you had settled up one coachful of aching weary men, by the knowledge that there were still hundreds to be attended to.

On the night of October 31 to November 1, No.7 Ambulance train had the luck, or ill-luck, to be on Ypres station – the date that marks the beginning of the wonderful first Battle of Ypres. The train received its baptism of fire that night – poor train – it could not have run away had it wanted to; the engine had returned down the line for water. A neighbouring improvised train loaded with minor wounded had better luck and secured an engine from somewhere, and, as it pulled out of the station into safety, I expect poor old No.7 heaved a small sigh of envy, although I like to think that even had a second engine been handy, No.7 would have stuck to her post; but with what feelings of great thankfulness and relief she hooked herself on to her engine the next morning, and gave him a graphic description of those horrid shells which had made holes in her sides and broken her windows, while he was away at Hazebrouck imbibing water.

After the establishment of Casualty Clearing Stations the work on ambulance trains was not nearly so arduous. In the first days patients were entrained with all the dirt, mud, and blood of battle on them. All were fully dressed. Many had not had their boots off their feet for five or six weeks. Only those who have experienced it, know what it means to undress a heavy man, badly wounded and lying on the narrow seat of a railway carriage. Never before had it bee brought home to me what a quantity of clothes a man wears. On many an occasion it has seemed a task worthy of a Hercules, but when the deed was done, the man undressed and in soft dry pyjamas, even though maybe there had only been time to sponge his face, hands, and feet – then indeed labour had its reward – the gratitude, the patience, the infinite endurance of the men was a constant marvel to behold. One felt that the utmost one could do was but a drop in the ocean of their discomfort, and their gratitude for that drop was sometimes more than one could bear.

Reminiscent Sketches

Sunday, 13 May 2007

Back to Heilly again for a moment...

Unchanged By Time

I added snippets of poetry to many of the pages, choosing each one to reflect some aspect of the man's life or service, and for the front page of the website I chose some lines which I had seen used in the 'In Memoriam' column of a local newspaper:

And now they are sleeping their long last sleep,

Their graves I may never see;

But some gentle hand in that distant land

May scatter some flowers for me.

I thought it summed up the feelings of families all over the world, particularly those who would never have the money or opportunity to visit the last resting place of their loved ones.

On my first visit to Heilly, a year or so later, the weather was stormy. The sky was ever-changing, with huge black clouds and heavy squalls accompanied by thunder and lightning. My daughter and I ran into the cemetery, and sat on the seat by the screen wall, sheltering until the current blast of rain had passed. Suddenly it stopped, and the sun broke through, shedding shards of light across the cemetery. I suppose my natural instinct was to follow the sun, and walked up to where it picked out vividly two or three headstones. As I stood in front of them I realised that I was looking at MY inscription [or a version of it] on the grave of Sapper David Simpson of the Australian Engineers:

in that distant land/will some kind hand/lay a flower/on his grave for me

I've visited a lot of cemeteries, but that day I did feel a very emotional attachment to Sapper Simpson, and hoped that for the sake of the family who left that message, I would remember on future visits to the cemetery to honour their wish.

Wednesday, 18 April 2007

Assistant Nurse

The grade of 'Assistant Nurse' became increasingly common, and these were women who had previously undertaken formal nurse training, but not to a standard sufficient to join Queen Alexandra's Imperial Nursing Service Reserve or the Territorial Force Nursing Service. They were women who had completed a set training as a fever nurse, a children's nurse, in a women's hospital, or as a midwife. Their pay fell half way between that of the VAD and the trained Staff Nurse, and they were likely to be given more responsibility in line with their training and experience.

While transcribing the war diary of the Matron-in-Chief with the British Expeditionary Force, I've now come across entries which show that this changed in 1918. The diary entry states:

V.A.D. Assistant Nurses: Received from Director General Medical Services copy of Army Council Instruction 214 of 1918 relating to the promotion of V.A.D. Members to the rank of

Assistant Nurses. Before being promoted they must have served two years, must be in possession of the Red Efficiency Stripe and must be recommended by the Officer Commanding and Matron. The letters "A.N." are to be worn on the apron in indoor uniform and on the shoulder straps on outdoor uniform.

The Red Efficiency Stripe was awarded to VAD members who had completed 13 months continuous service in a military hospital under the control of the War Office, and who had satisfactory confidential reports by their Matron and Commanding Officer. After another years' service they could qualify for a second stripe. These stripes should not be confused with the white stripes often seen on the sleeves of VADs, which signified length of service alone, not that they had necessarily reached a high standard in their work [although of course they might have done!].

Friday, 6 April 2007

Who has the truth?

I’ve got used to reading a fair amount of inaccuracy about nursing during the Great War. Well, that’s not quite true – I almost expect it now, although I’ve never got USED to it – and when I come across bits that are blatant rubbish, they really rankle, especially if they’re written by academics, as these are the accounts that may well be digested and then repeated as the absolute truth.

As a member of the Royal College of Nursing, the newsletter of the associated History of Nursing Society dropped through my letter box last week. Inside was a short article written by a prominent member of the nursing profession, titled ‘Who has the truth?’ In it she expresses regret that the health care professions are failing to keep much of their paperwork and written archive material, and also of the transient nature of electronic sources which are too easily deleted, a process that she describes as ‘throwing our “truth" away’. She makes a comparison with the diaries and letters retained by Vera Brittain, which allowed her, nearly two decades later, to ‘write an accurate testimony’ of her life as a VAD during the Great War.

How accurate those original diaries were, and whether we are throwing out history away now, any more than we did a hundred years ago, are both subjects which could be long debated, but I was interested in one paragraph, in which she writes:

A Testament of Youth kept us fixed to our TV screens in the 1970s as we followed this amazing woman through her Voluntary Aided Detachment (VAD) experiences in the First World War. Through her memory, supported by diaries, letters and “artefacts”, she gives subsequent generations insight into the experience of living through those times. She lost her fiancé, her brother, their friends and many, many patients. She nursed on the Western Front, in Malta and everywhere in between in field ambulances and hospital trains.

That last sentence made me sit up and take notice, and, very concerned that my memory might be failing me in advancing years, it had me running to grab my copies of “Testament of Youth” and “Chronicle of Youth.” Vera Brittain certainly served on the Western Front and in Malta, but where was this ‘everywhere in between’ that is mentioned. No VAD member working under the auspices of the War Office [as Brittain was] ever served in a casualty clearing station, let alone a field ambulance, their service being restricted to military hospitals only, and military ambulance trains carried a staff of three trained nurses, not VADs. So did VB make any claims in her writing to working in field ambulances or on ambulance trains? Did the filmed version of “Testament of Youth” use artistic licence to include scenes that could not be substantiated by original sources? Or has the writer included that sentence to make more interesting reading without having intimate knowledge of her subject? I’d be glad for any further insights into this.

‘Who has the truth?’

Friday, 23 March 2007

Marriage

I often see queries asking whether nurses serving with the British Army during the Great War could be married. The answer is, of course, rather a complicated one. Prior to the Great War, women training to be nurses were required to be either single, or widowed, although it was not too difficult for a married woman with no dependants and living apart from her husband to stretch the truth. But in general, nursing, like teaching, was a profession of single women, and they were required to resign their appointments on marriage.

At the outbreak of war, all the members Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service, numbering just over 300, were single, and although there were a few members of the Territorial Force Nursing Service who were married, this had occurred during their civil employment, and on mobilisation many chose to resign, or were retained for home service only. The intention of the Matron-in-Chief at the War Office was to keep the services staffed by single women, but this proved to be impossible. By the middle of 1915 the shortage of trained nurses, both at home and abroad was acute, and it was obvious that it would be necessary to retain the services of women upon marriage, unless they wished to resign. At first they were sent home from France, for ‘Home Service only’, and Maud McCarthy, the Matron-in-Chief with the British Expeditionary Force thought that she would never get hard work and devotion to duty from women who had more than nursing on their minds. She was particularly opposed to married nurses and VADs who wished to work in France because their husbands were serving there, and described them as women with ‘their baggage at the Front.’ As the manpower shortage increased, marriage was looked upon rather more benevolently, and it was eventually agreed that as long as a woman informed the military authorities of her forthcoming marriage; observed all the correct formalities, and had good reports, she would be allowed to continue to serve, and remain overseas if she wished. Any woman who went on leave, and married in England without permission, would find herself looked on unfavourably, and probably refused permission to return to France, especially if she was a VAD, who were more easily recruited and not in such short supply.

Reading through the war diary of the Matron-in-Chief, it often seems as though there were many marriages happening at extremely short notice – the sort of ‘spur of the moment’ occurrences that wartime is famous for. I suspect that the phrase ‘marry in haste, repent at leisure’ haunted many a nurse throughout her life! And if the British military nursing authorities seemed very straight-laced about marriage, they could not compare with the Australians. Until the middle of 1917, a member of the Australian Army Nursing Service did not even have to bother to resign on marriage, as at that point her contract was automatically terminated, and she was returned to the UK, to continue her life as she chose – but of course, eventually the shortage of trained nurses changed that as well, and marriage became a necessary wartime evil for the AANS.

After the war, as the demobilization of nurses working on the QAIMNS Reserve was complete, the service returned to one of single women, a situation which lasted until the 1970s. Even married members of the Territorial Force Nursing Service, who returned to their civil employment, were not allowed to remain in the service – what was useful in wartime was found unacceptable in peacetime.

Tuesday, 6 March 2007

The Difference Between...

VADs were employed by the British Red Cross Society through their headquarters at Devonshire House, and the majority worked in Red Cross and auxiliary hospitals, but if employed in British military hospitals at home or abroad, they would work under the control of the War Office, and take their day to day orders from the Matron of their hospital or her deputies.

Special Military Probationers were also untrained, and the terms and conditions of their contracts were virtually identical to those of the VAD. But they were employed by the War Office specifically to work in military hospitals, and had no connection with the BRCS. There is some evidence to suggest that the War Office did some 'cherry picking' - during the 3 month initial training undertaken by VADs in civil hospitals from 1915 onwards, some of the most able were offered contracts as SMPs, and the result was the perception that these 'War Probationers' formed a more elite group than the VADs. In fact, except for the difference in employers, their contracts and conditions of service were identical, but there always remained the inference that those employed by the War Office were superior as nurses.

As the need for trained nurses grew during the war, shortages began to cause great difficulties, particularly overseas, where the need for skilled nurses in forward areas resulted in Base hospitals becoming top heavy with VADs, and seriously lacking in experienced women. The grade of 'Assistant Nurse' became increasingly common, and these were women who had previously undertaken formal nurse training, but not to a standard sufficient to join Queen Alexandra's Imperial Nursing Service Reserve or the Territorial Force Nursing Service. They were women who had completed a set training as a fever nurse, a children's nurse, in a women's hospital, or as a midwife. Their pay fell half way between that of the VAD and the trained Staff Nurse, and they were likely to be given more responsibility in line with their training and experience.

As the war progressed, there were certainly VADs who became very skilled nurses and took on great responsibility. Many had hopes that their wartime work would qualify them for a reduced training as a nurse after the war, and that was a question that caused great unrest and discussion within the nursing profession. And was definitely not to be...

Tuesday, 27 February 2007

Nurses' Service Records at TNA

But quite a number were totally destroyed - no-one really knows how many, or why certain files were chosen for destruction, while others survived. It's been suggested that there might be as many as 5,000 missing, but I find that difficult to believe, otherwise I would find that about 1 in 4 of those I look for are missing, which just isn't the case. I frequently draw a blank with service records, without understanding the reason, but recently I've failed to find a couple, which has proved quite helpful in one way, as it's highlighted one class of woman whose files are likely to have been scrapped. Both these women were members of the Territorial Force Nursing Service; they served during wartime, but were discharged from the service soon after the war; they had no entitlement to pension, and they both died during the 1920s from causes unrelated to their war service. As they were not going to serve at any time in the future, no pensions, and a non-attributable cause of death, it looks as though retention of their service files was considered unnecessary.

It will be interesting to try and pinpoint other groups of women whose files were similarly afflicted - finding a whole missing group would be a useful aid understanding the system.

Thursday, 22 February 2007

Heilly Station

Heilly today seems a hauntingly sad place, in countryside that looks untouched by tragedy. But life goes on, and when I was there last year, the station-master was proud to tell us that his station is on the present day route of the TGV [Train Grand Vitesse] and also sees the Orient Express go through twice a week [once each way], although neither actually stop there. No more casualties in or out of Heilly Station! He also said that field walking constantly turns up mementoes of those wartime days.

So here is Heilly today, the station; the site of the casualty clearing stations, and the military cemetery, the last resting place of 2,890 Commonwealth soldiers, and 83 Germans.

Just click on the photos to enlarge them

**************

Saturday, 17 February 2007

Where on earth was that?

If you've found mention of a hospital or casualty clearing station in France and Flanders by it's number, and have no idea where it was situated, there is a way to track it down. In 1923, the Ministry of Pensions published a booklet entitled:

'Location of Hospitals and Casualty Clearing Stations: British Expeditionary Force 1914-1919'

and it's now available online here:

http://www.vlib.us/medical/CCS/ccs.htm

It's quite a long document, and it takes some scrolling up and down to find what you're looking for, and remember it only covers the Western Front, not any other theatre of war, such as Salonika or Mesopotamia. Also beware that there are quite a few errors and omissions - wrong dates, places, and in a few cases entire units missing. But still a really helpful publication.

As an anorak wearer of some distinction, I've put the information into five spreadsheets - hospitals by number, hospitals by location, and the same for the casualty clearing stations, with the fifth being for British Red Cross units. As I find more information, I can then add corrections, and have ended up with some very workable documents.

Well, if that's the sort of thing that grabs you ...The Casualty Clearing Station

The following page is a great example of appalling inaccuracy, with no easy way to contact the author to report their trial and execution (by ME!).

http://www.oucs.ox.ac.uk/ltg/projects/jtap/dce/ritchie/ClearingStations.html

http://www.chavasse.u-net.com/ccs.html

[Link now removed]

Entitled 'A Casualty Clearing Station at Trones Wood, August 1916' the photo is obviously genuine, but is not a Casualty Clearing Station, but some sort of medical facility right on the front line - an advanced dressing station, or regimental aid post. The amount of incorrect information is prodigious, but even reputable sites don't get it right - they have a go, but seem to be working from documents that simply don't reflect what was actually happening on the ground at the time.

The Western Front Association tell us that a CCS had 'a nominal capacity of 150' while the Victoria and Albert Museum describe them as 'small mobile hospitals' and a recent edition of The National Archives magazine 'Ancestors' carried a wonderfully illustrated article on the life and work of VADs in Casualty Clearing Stations on the Western Front. Just to emphasise the point, VADs were never allowed to be employed in any CCS. Never, ever. I did write to TNA just to let them know that their lead article was just not right, but unfortunately they neither replied to me, nor did they publish a correction.

In the autumn of 1914, when the war became static, Casualty Clearing Stations shed their extreme mobility and started to spring up in more fixed form, near enough to the front line to be easily accessible, but out of range of most of the German artillery. They were, wherever possible, established in buildings; convents, schools, factories and existing hospitals, often expanding into huts and tents to provide more accommodation. Later on, many became predominately tented and hutted, but only in the absence of suitable permanent accommodation. Trained nurses were posted to CCSs from October 1914, and to certain Field Ambulances from the autumn of 1915. Only the most experienced nursing staff were sent, and were immediately replaced if they proved lacking in the many qualities needed. In the early days, four nurses were considered adequate in addition to the RAMC staff, but by August 1916 some CCSs had nursing staffs of 25 to cope with the enormous casualties of the battles of the Somme.

At present I'm transcribing the official war diary of the Matron-in-Chief with the British Expeditionary Force in France and Flanders during the Great War. It runs to more than 4,000 pages, and hopefully it will provide enough material of interest to enable it to be published, albeit in much edited form. But just for the sake of waving the flags of both the Casualty Clearing Station, and it's smaller brother the Field Ambulance, here are some extracts taken at random from the diary, during the spring and summer of 1916. These are just a few of thousands of similar entries, but hopefully will provide an accurate snapshot of the set-up and conditions at CCSs and FAs at that time, as viewed through the eyes of the Matron-in-Chief, Maud McCarthy, on her visits of inspection. Although I have removed some of the diary entries not relevant to Casualty Clearing Stations, I have left the remaining text as originally written, and without correction or editing. I will let them stand alone, without further comment.

Warloy 92 Field Ambulance. More help, only Staff of 4 and they had been working day and night.

Puchevillers 3 and 44 C.C. Station busy opening up under canvas. They are side by side, quite close to a railway side and both Staff will Mess together. Arrangements very good.

Authie South Midland Field Ambulance, in a Chateau, Staff not yet arrived, but everything being got into order, and good accommodation for Staff ready. Some very badly wounded there, who were being cared for devotedly by the orderlies – even flowers by their sides.

Doullens The Citadelle – a wonderful historic fort, inside which 35 C.C. Station is being established. Wonderful buildings, a Chateau, Barracks, etc., built 1618. Anxiously waiting for Staff which should arrive tonight.

(Welsh F.A.) To Authie to Field Ambulance also just arriving, the predecessor just transferred to Warloy. Here the work had diminished considerably, and I found I was able to move 4 Nurses.

To Doullens to Citadelle, 11 and 35 C.C. Station. This place in the short time has become a most magnificent unit, more like a General Hospital than a C.C. Station in every respect. Miss Toller who is in charge of both units is managing most excellently. In all instances I saw the O.C.s who expressed entire satisfaction with the Nursing arrangements in all units.

Wednesday, 14 February 2007

Not what is required

From the first days of the Army Nursing Service, the Army had insisted not only on a good training, but in addition, that their candidates should have good social standing. After the formation of Queen Alexandra's Imperial Military Nursing Service in 1902, and the expansion of the military nursing service, many women applied to enter, but so few were considered acceptable that it was always a fight to maintain the required establishment. With their form of application they had to supply three references, one from the Matron of their training institution, and at least one other from a 'lady' known personally to the candidate, and who could vouch for her suitability.

Some candidates fell by the wayside because her even her 'lady' was not considered adequately furnished with the right qualities, but many, having been invited to interview, fell foul of all sorts of social prejudices. The minutes of the Nursing Board, held at the National Archives, report in detail on the reasons for non-acceptance of candidates in 1902-4:

* Miss L. D. Apparent want of social standing, and appearance unsuitable.

* Miss M. F. Social status and behaviour not suitable.

* Miss M. M. Social status unsuitable from all reports, and education imperfect.

* Miss L. V. Her appearance and style not at all what is required in an Army Nurse.

* Miss M. M. Quite unsuitable. Father an iron-plate worker, mother cannot sign her name.

* Miss E. S. Unsuitable from her parentage. Father a shoemaker.

* Miss M. B. Common style and manner.

* Miss W. Unsuitable for the service. Is a coloured lady from America.

And so on - columns of them. Many of these women had already served with the Army Nursing Service Reserve during the Boer War, but mention of their past nursing abilities rarely occurs. Perhaps this lack of tact and discretion finally dawned on them, as in June 1904, an entry in the minute book states:

The Board resolved that in the remarks as to the cause of rejection of candidates, observations as to their social status should in future be replaced by a statement such as 'Not considered suitable' or 'Not recommended'.

The practice continued, of course, but was simply no longer written about. And it continued right up to the Great War, that great comma, that changed a lot of things in British life. But it always amuses me to realise that perhaps not as much changed as it seems. When I joined Queen Alexandra's Royal Army Nursing Corps in the 1970s, my father, an ex-Army Warrant Officer, was working as a stores manager at Vauxhall Motors. Looking over my shoulder, while I sat filling in my application form, my mother jumped six feet:

'No dear, you can't possibly put that - it sounds so common'.

So after much deliberation and discussion, my form was submitted, and written in the space for father's occupation was 'Account Manager, Motor Company'. Definitely not the first, and surely not the last to supply a white lie to the War Office?

Sunday, 11 February 2007

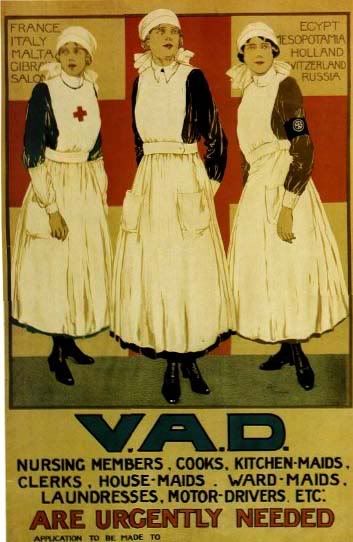

The V.A.D.

I used to think I didn't like VADs very much. After all, I'm a trained nurse, and felt a bit put out that they barged their way into the war without a please or a thank you, and later wrote rather prolifically about how they were pivotal in the winning of it. Since then I've mellowed considerably, but at the time, they came in for plenty of flack from some quarters.

In 1914, the nursing profession was in a state of upheaval, with various factions campaigning for the training and registration of nurses to fall into line with their particular views. A three year training in a large general hospital had become the accepted gold standard for the professional nurse - three years of long hours, strict discipline, and extreme hard work, followed perhaps by more years of the same; climbing the ladder of experience and responsibility.

So hardly surprising that when it was first mooted that untrained women (whisper it... VADs...) would be employed in military hospitals at home and abroad, there was great unrest among most trained military nurses, and by the nursing press. They were adamant that they simply would not allow their patients to endure the second class care that would be dished out by these clueless young upstarts - 'Ils ne passeront pas' springs to mind.

The VADs, for their part, were often well-bred, educated young women, with attributes (to their eyes) unknown in the ranks of the Army nurse. They were enthusiastic, and the War Office took care to select only the best to go overseas, but there were frequent conflicts between the two factions. It seems one of those strange facts that while VADs wrote many memoirs about their experiences during the Great War, the trained nurse left virtually none, so the picture that remains is a bit one-sided. Perhaps the VAD looked on the experience as a special time in her life, which stood out, and was worthy of reflection and description, whereas to the professional it was just another aspect of an already full career. There are several stinging descriptions of Army nursing sisters by Enid Bagnold, Olive Dent, and Vera Brittain - about those I will expand another time.

But do I like VADs now? Yes, I have to admit that we couldn't have kept our military hospitals running without them, and the nursing services both at home and abroad would have collapsed if they had relied solely on the professional. Trained nurses took three years to produce. VADs took, at most, three months. There are good and bad in all walks of life, but the VADs came forward in abundance, gave of their best, and in the main were simply splendid.

Saturday, 10 February 2007

Training

Most nurses practising today have gone through a three year training. Some have extended that period with a few additional bells and whistles, but in the main, a three year training has been the 'norm' for a long time, although the content of that training has varied, and gone up and down with the hemlines. But training wasn't always like that. In fact, there was a time when training 'wasn't' at all.

Until the Nurses Registration Act of 1919, there was no registration of nurses, no regulation or standardisation of training, no examination to prove, or dis-prove competence. Anyone could call themselves a nurse, and as long as they worked within the law, that could not be challenged.

Florence Nightingale fired the starting pistol of nurse training when she opened her school at St. Thomas' Hospital in 1860. Her mixture of 'ladies' and probationers underwent a one year training in order to receive their hospital certificate, and until the 1880s, this one year was considered adequate time to produce a woman capable of meeting all the challenges that hospital and home nursing would throw at her. But by the 1880s, suggestions came from several quarters that this period should be extended, and in 1887 the British Nurses Association started to campaign both for a three year training, and also for national standards to be laid down.

At the turn of the century, there existed a confusing mixture of women, some of whom had a one year's certificate; some a three year training, which could have been good or bad; some a one or two year training in children's or fever nursing; some in the words of Brian Abel-Smith had learned their trade 'on the hedgerow of experience.' But there had developed an unofficial 'gold standard' which laid down that a full training of the best kind came from three years in a general hospital of more than one hundred beds.

When Queen Alexandra's Imperial Military Nursing Service came into being on 27 March 1902, it employed the strictest standards. Not only did it insist on the full three year training, but also that it's applicants met the highest standards of educational attainment and social standing. With so few women in Great Britain even coming close to meeting that standard, they always struggled to maintain their full establishment. But they were never willing, for a moment, to let those standards slip. In 1902, there was already an Army Nursing Service, many of the nursing sisters had years of devoted service in military hospitals, but even they had to re-apply to be accepted by the new service, and prove that they were fit to continue to serve the Army.

One of those women, Isabella Jerrard, was in for quite a shock, when she applied to transfer to the new service in 1902. At that time she had served for 24 years and 2 months in the Army Nursing Service, reaching the rank of Superintendent (equivalent to a Matron), but (Oh horror!) it was discovered that she had never received nurse training of any kind, and therefore could not be allowed to transfer to QAIMNS.

However, shortly afterwards, her case was reconsidered, and the Advisory Board recommended:

In admitting candidates from the existing Service, the Advisory Board thinks that regard should be paid rather to the manner in which they have performed their duties as Army Nursing Sisters than to the qualifications required of them at the date of their admittance to that Service.

The Nursing Board had to make a U-turn, and find a place for this middle-aged maverick, and in confirming her position as a Matron in QAIMNS stated:

The Nursing Board desires to inform the Advisory Board that Miss Jerrard was declined for QAIMNS, not only on the grounds of insufficient training, but because the evidence before the Selecting Committee made it clear that she was not suited for the post of Matron – the only position in the Service for which she could be considered eligible after her 24 years’ service. On reconsidering the case the Nursing Board, on account of her age and long service, is willing to recommend that Miss Jerrard be retained in her present position until she has completed the period necessary for the pension due at 50 years of age.

This case is a good example of how a three year training had become the standard for the professional nurse, and one which even in 1902, the Army would insist on above all other considerations.