Tuesday, 27 February 2007

Nurses' Service Records at TNA

But quite a number were totally destroyed - no-one really knows how many, or why certain files were chosen for destruction, while others survived. It's been suggested that there might be as many as 5,000 missing, but I find that difficult to believe, otherwise I would find that about 1 in 4 of those I look for are missing, which just isn't the case. I frequently draw a blank with service records, without understanding the reason, but recently I've failed to find a couple, which has proved quite helpful in one way, as it's highlighted one class of woman whose files are likely to have been scrapped. Both these women were members of the Territorial Force Nursing Service; they served during wartime, but were discharged from the service soon after the war; they had no entitlement to pension, and they both died during the 1920s from causes unrelated to their war service. As they were not going to serve at any time in the future, no pensions, and a non-attributable cause of death, it looks as though retention of their service files was considered unnecessary.

It will be interesting to try and pinpoint other groups of women whose files were similarly afflicted - finding a whole missing group would be a useful aid understanding the system.

Thursday, 22 February 2007

Heilly Station

Heilly today seems a hauntingly sad place, in countryside that looks untouched by tragedy. But life goes on, and when I was there last year, the station-master was proud to tell us that his station is on the present day route of the TGV [Train Grand Vitesse] and also sees the Orient Express go through twice a week [once each way], although neither actually stop there. No more casualties in or out of Heilly Station! He also said that field walking constantly turns up mementoes of those wartime days.

So here is Heilly today, the station; the site of the casualty clearing stations, and the military cemetery, the last resting place of 2,890 Commonwealth soldiers, and 83 Germans.

Just click on the photos to enlarge them

**************

Saturday, 17 February 2007

Where on earth was that?

If you've found mention of a hospital or casualty clearing station in France and Flanders by it's number, and have no idea where it was situated, there is a way to track it down. In 1923, the Ministry of Pensions published a booklet entitled:

'Location of Hospitals and Casualty Clearing Stations: British Expeditionary Force 1914-1919'

and it's now available online here:

http://www.vlib.us/medical/CCS/ccs.htm

It's quite a long document, and it takes some scrolling up and down to find what you're looking for, and remember it only covers the Western Front, not any other theatre of war, such as Salonika or Mesopotamia. Also beware that there are quite a few errors and omissions - wrong dates, places, and in a few cases entire units missing. But still a really helpful publication.

As an anorak wearer of some distinction, I've put the information into five spreadsheets - hospitals by number, hospitals by location, and the same for the casualty clearing stations, with the fifth being for British Red Cross units. As I find more information, I can then add corrections, and have ended up with some very workable documents.

Well, if that's the sort of thing that grabs you ...The Casualty Clearing Station

The following page is a great example of appalling inaccuracy, with no easy way to contact the author to report their trial and execution (by ME!).

http://www.oucs.ox.ac.uk/ltg/projects/jtap/dce/ritchie/ClearingStations.html

http://www.chavasse.u-net.com/ccs.html

[Link now removed]

Entitled 'A Casualty Clearing Station at Trones Wood, August 1916' the photo is obviously genuine, but is not a Casualty Clearing Station, but some sort of medical facility right on the front line - an advanced dressing station, or regimental aid post. The amount of incorrect information is prodigious, but even reputable sites don't get it right - they have a go, but seem to be working from documents that simply don't reflect what was actually happening on the ground at the time.

The Western Front Association tell us that a CCS had 'a nominal capacity of 150' while the Victoria and Albert Museum describe them as 'small mobile hospitals' and a recent edition of The National Archives magazine 'Ancestors' carried a wonderfully illustrated article on the life and work of VADs in Casualty Clearing Stations on the Western Front. Just to emphasise the point, VADs were never allowed to be employed in any CCS. Never, ever. I did write to TNA just to let them know that their lead article was just not right, but unfortunately they neither replied to me, nor did they publish a correction.

In the autumn of 1914, when the war became static, Casualty Clearing Stations shed their extreme mobility and started to spring up in more fixed form, near enough to the front line to be easily accessible, but out of range of most of the German artillery. They were, wherever possible, established in buildings; convents, schools, factories and existing hospitals, often expanding into huts and tents to provide more accommodation. Later on, many became predominately tented and hutted, but only in the absence of suitable permanent accommodation. Trained nurses were posted to CCSs from October 1914, and to certain Field Ambulances from the autumn of 1915. Only the most experienced nursing staff were sent, and were immediately replaced if they proved lacking in the many qualities needed. In the early days, four nurses were considered adequate in addition to the RAMC staff, but by August 1916 some CCSs had nursing staffs of 25 to cope with the enormous casualties of the battles of the Somme.

At present I'm transcribing the official war diary of the Matron-in-Chief with the British Expeditionary Force in France and Flanders during the Great War. It runs to more than 4,000 pages, and hopefully it will provide enough material of interest to enable it to be published, albeit in much edited form. But just for the sake of waving the flags of both the Casualty Clearing Station, and it's smaller brother the Field Ambulance, here are some extracts taken at random from the diary, during the spring and summer of 1916. These are just a few of thousands of similar entries, but hopefully will provide an accurate snapshot of the set-up and conditions at CCSs and FAs at that time, as viewed through the eyes of the Matron-in-Chief, Maud McCarthy, on her visits of inspection. Although I have removed some of the diary entries not relevant to Casualty Clearing Stations, I have left the remaining text as originally written, and without correction or editing. I will let them stand alone, without further comment.

Warloy 92 Field Ambulance. More help, only Staff of 4 and they had been working day and night.

Puchevillers 3 and 44 C.C. Station busy opening up under canvas. They are side by side, quite close to a railway side and both Staff will Mess together. Arrangements very good.

Authie South Midland Field Ambulance, in a Chateau, Staff not yet arrived, but everything being got into order, and good accommodation for Staff ready. Some very badly wounded there, who were being cared for devotedly by the orderlies – even flowers by their sides.

Doullens The Citadelle – a wonderful historic fort, inside which 35 C.C. Station is being established. Wonderful buildings, a Chateau, Barracks, etc., built 1618. Anxiously waiting for Staff which should arrive tonight.

(Welsh F.A.) To Authie to Field Ambulance also just arriving, the predecessor just transferred to Warloy. Here the work had diminished considerably, and I found I was able to move 4 Nurses.

To Doullens to Citadelle, 11 and 35 C.C. Station. This place in the short time has become a most magnificent unit, more like a General Hospital than a C.C. Station in every respect. Miss Toller who is in charge of both units is managing most excellently. In all instances I saw the O.C.s who expressed entire satisfaction with the Nursing arrangements in all units.

Wednesday, 14 February 2007

Not what is required

From the first days of the Army Nursing Service, the Army had insisted not only on a good training, but in addition, that their candidates should have good social standing. After the formation of Queen Alexandra's Imperial Military Nursing Service in 1902, and the expansion of the military nursing service, many women applied to enter, but so few were considered acceptable that it was always a fight to maintain the required establishment. With their form of application they had to supply three references, one from the Matron of their training institution, and at least one other from a 'lady' known personally to the candidate, and who could vouch for her suitability.

Some candidates fell by the wayside because her even her 'lady' was not considered adequately furnished with the right qualities, but many, having been invited to interview, fell foul of all sorts of social prejudices. The minutes of the Nursing Board, held at the National Archives, report in detail on the reasons for non-acceptance of candidates in 1902-4:

* Miss L. D. Apparent want of social standing, and appearance unsuitable.

* Miss M. F. Social status and behaviour not suitable.

* Miss M. M. Social status unsuitable from all reports, and education imperfect.

* Miss L. V. Her appearance and style not at all what is required in an Army Nurse.

* Miss M. M. Quite unsuitable. Father an iron-plate worker, mother cannot sign her name.

* Miss E. S. Unsuitable from her parentage. Father a shoemaker.

* Miss M. B. Common style and manner.

* Miss W. Unsuitable for the service. Is a coloured lady from America.

And so on - columns of them. Many of these women had already served with the Army Nursing Service Reserve during the Boer War, but mention of their past nursing abilities rarely occurs. Perhaps this lack of tact and discretion finally dawned on them, as in June 1904, an entry in the minute book states:

The Board resolved that in the remarks as to the cause of rejection of candidates, observations as to their social status should in future be replaced by a statement such as 'Not considered suitable' or 'Not recommended'.

The practice continued, of course, but was simply no longer written about. And it continued right up to the Great War, that great comma, that changed a lot of things in British life. But it always amuses me to realise that perhaps not as much changed as it seems. When I joined Queen Alexandra's Royal Army Nursing Corps in the 1970s, my father, an ex-Army Warrant Officer, was working as a stores manager at Vauxhall Motors. Looking over my shoulder, while I sat filling in my application form, my mother jumped six feet:

'No dear, you can't possibly put that - it sounds so common'.

So after much deliberation and discussion, my form was submitted, and written in the space for father's occupation was 'Account Manager, Motor Company'. Definitely not the first, and surely not the last to supply a white lie to the War Office?

Sunday, 11 February 2007

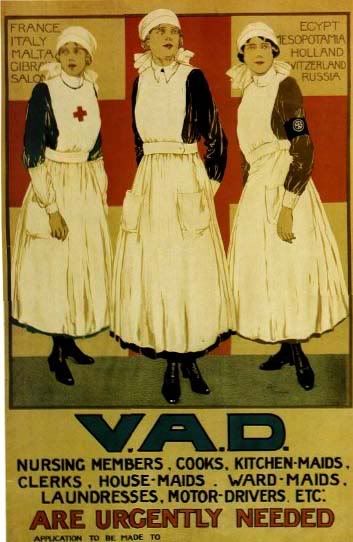

The V.A.D.

I used to think I didn't like VADs very much. After all, I'm a trained nurse, and felt a bit put out that they barged their way into the war without a please or a thank you, and later wrote rather prolifically about how they were pivotal in the winning of it. Since then I've mellowed considerably, but at the time, they came in for plenty of flack from some quarters.

In 1914, the nursing profession was in a state of upheaval, with various factions campaigning for the training and registration of nurses to fall into line with their particular views. A three year training in a large general hospital had become the accepted gold standard for the professional nurse - three years of long hours, strict discipline, and extreme hard work, followed perhaps by more years of the same; climbing the ladder of experience and responsibility.

So hardly surprising that when it was first mooted that untrained women (whisper it... VADs...) would be employed in military hospitals at home and abroad, there was great unrest among most trained military nurses, and by the nursing press. They were adamant that they simply would not allow their patients to endure the second class care that would be dished out by these clueless young upstarts - 'Ils ne passeront pas' springs to mind.

The VADs, for their part, were often well-bred, educated young women, with attributes (to their eyes) unknown in the ranks of the Army nurse. They were enthusiastic, and the War Office took care to select only the best to go overseas, but there were frequent conflicts between the two factions. It seems one of those strange facts that while VADs wrote many memoirs about their experiences during the Great War, the trained nurse left virtually none, so the picture that remains is a bit one-sided. Perhaps the VAD looked on the experience as a special time in her life, which stood out, and was worthy of reflection and description, whereas to the professional it was just another aspect of an already full career. There are several stinging descriptions of Army nursing sisters by Enid Bagnold, Olive Dent, and Vera Brittain - about those I will expand another time.

But do I like VADs now? Yes, I have to admit that we couldn't have kept our military hospitals running without them, and the nursing services both at home and abroad would have collapsed if they had relied solely on the professional. Trained nurses took three years to produce. VADs took, at most, three months. There are good and bad in all walks of life, but the VADs came forward in abundance, gave of their best, and in the main were simply splendid.

Saturday, 10 February 2007

Training

Most nurses practising today have gone through a three year training. Some have extended that period with a few additional bells and whistles, but in the main, a three year training has been the 'norm' for a long time, although the content of that training has varied, and gone up and down with the hemlines. But training wasn't always like that. In fact, there was a time when training 'wasn't' at all.

Until the Nurses Registration Act of 1919, there was no registration of nurses, no regulation or standardisation of training, no examination to prove, or dis-prove competence. Anyone could call themselves a nurse, and as long as they worked within the law, that could not be challenged.

Florence Nightingale fired the starting pistol of nurse training when she opened her school at St. Thomas' Hospital in 1860. Her mixture of 'ladies' and probationers underwent a one year training in order to receive their hospital certificate, and until the 1880s, this one year was considered adequate time to produce a woman capable of meeting all the challenges that hospital and home nursing would throw at her. But by the 1880s, suggestions came from several quarters that this period should be extended, and in 1887 the British Nurses Association started to campaign both for a three year training, and also for national standards to be laid down.

At the turn of the century, there existed a confusing mixture of women, some of whom had a one year's certificate; some a three year training, which could have been good or bad; some a one or two year training in children's or fever nursing; some in the words of Brian Abel-Smith had learned their trade 'on the hedgerow of experience.' But there had developed an unofficial 'gold standard' which laid down that a full training of the best kind came from three years in a general hospital of more than one hundred beds.

When Queen Alexandra's Imperial Military Nursing Service came into being on 27 March 1902, it employed the strictest standards. Not only did it insist on the full three year training, but also that it's applicants met the highest standards of educational attainment and social standing. With so few women in Great Britain even coming close to meeting that standard, they always struggled to maintain their full establishment. But they were never willing, for a moment, to let those standards slip. In 1902, there was already an Army Nursing Service, many of the nursing sisters had years of devoted service in military hospitals, but even they had to re-apply to be accepted by the new service, and prove that they were fit to continue to serve the Army.

One of those women, Isabella Jerrard, was in for quite a shock, when she applied to transfer to the new service in 1902. At that time she had served for 24 years and 2 months in the Army Nursing Service, reaching the rank of Superintendent (equivalent to a Matron), but (Oh horror!) it was discovered that she had never received nurse training of any kind, and therefore could not be allowed to transfer to QAIMNS.

However, shortly afterwards, her case was reconsidered, and the Advisory Board recommended:

In admitting candidates from the existing Service, the Advisory Board thinks that regard should be paid rather to the manner in which they have performed their duties as Army Nursing Sisters than to the qualifications required of them at the date of their admittance to that Service.

The Nursing Board had to make a U-turn, and find a place for this middle-aged maverick, and in confirming her position as a Matron in QAIMNS stated:

The Nursing Board desires to inform the Advisory Board that Miss Jerrard was declined for QAIMNS, not only on the grounds of insufficient training, but because the evidence before the Selecting Committee made it clear that she was not suited for the post of Matron – the only position in the Service for which she could be considered eligible after her 24 years’ service. On reconsidering the case the Nursing Board, on account of her age and long service, is willing to recommend that Miss Jerrard be retained in her present position until she has completed the period necessary for the pension due at 50 years of age.

This case is a good example of how a three year training had become the standard for the professional nurse, and one which even in 1902, the Army would insist on above all other considerations.

Thursday, 8 February 2007

My Grandmother Nursed on the Somme

The area of France officially called the Somme is quite large, extending in the west to the coast beyond Abbeville, and south to Montdidier, but for the British it almost always refers to that much smaller area of the Departement north of the River Somme, and east of Amiens, which was the scene of fierce fighting in 1916, and again two years later.

Most nurses, both trained and untrained, who worked under the auspices of the British Army, were employed in hospitals far back from the fighting, in Boulogne, Le Havre, Abbeville, Rouen, Etaples, and many points on the coast. Although technically some women were 'on the Somme,' they were far removed from trench warfare, [although later in the war did not escape German bombing raids], and were not giving aid to men in the trenches of the Somme battlefield.

A few nurses, specially chosen for their stamina, skill, and aptitude for 'acute' work, took their turn in staffing Casualty Clearing Stations, located nearer the front line, and even fewer in Field Ambulances, which might be only a couple of miles away from the fighting, but they would quickly be withdrawn if their situation became too hazardous. The majority of nurses spent most of their time 'at the Base,' working in large British military general and stationary hospitals with a constant turnover of both wounded men, and those suffering from common complaints and infectious diseases. Untrained women - members of Voluntary Aid Detachments [VADs], never worked anywhere other than hospital - no untrained nurse was ever permitted to go to a Casualty Clearing Station, however short-handed they were.

If your relative did go overseas during the Great War, and worked in units under the control of the British Army, she would have qualified for service medals, and should have a medal index card at The National Archives. This index is searchable online, and doesn't give a lot of information, but does confirm overseas service and unit. You'll find it at:

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documentsonline/

Click on the search button, and then on 'WW1 Campaign Medals'.

So if grandmother was attached to the British army, the likelihood is that she didn't see a lot of the Somme, other than gazing over the western reaches close to Abbeville. Mind you, she would have still have seen things that most of us could never even imagine.

Wednesday, 7 February 2007

A New Beginning

www.scarletfinders.co.uk

I thought it might be useful to add informal comment and information about military nurses, and provide a platform to describe far more about their lives, training, and their place in army hospitals during the first quarter of the twentieth century. Unfortunately, although it looked rather beautiful, it proved inflexible as regards font size [only one] formatting [not much] and it scattered odd HTML code around rather freely in some browsers, which must have led people to believe that I don't know what I'm doing [I don't].

So I've decided to swap it over, and some of this blog's early writing will be taken directly from the original, so if you think you've read it before, you might have, but it you persevere, there might eventually be something new!